hmongmentalk2020

Giveaway

Annoucing the winner fb live 6/16/20

To enter click above

Below are the 3 prize: watch, necktie and tie clip

A video on how to enter and win

Last Mother's giveaway

Daniel Lee

Daniel Lee

Unapologetically Hmong. Actor/Director/Writer/Producer with Good Zoo Studios. IG/Twitter: @mrdaniellee

- White Proximity and Anti-Blackness

From: Daniel LeeTo: Hmong-AmericansSubject: White proximity and Anti-BlacknessHey. Nyob zoo. I see you.I’m sure you’ve seen the videos and news articles about #GeorgeFloyd and his terrible murder at the hands of Officer Derek Chauvin. I’m sure you’ve seen the increased mention of Officer Tou Thao, who stood by with hands by his side as George Floyd’s life slipped away.“He was just doing his job”, “have you heard of the ‘blue wall of silence’”, “not all cops”. CUT THE BULLSHIT.I’ve heard it millions of times before. Hell, I probably used to peddle it too. But every day is an opportunity to learn. Hiding behind your privilege and white proximity will not protect you. While you may feel that you’re a better citizen than black people, understand that you are not. You’re a posterchild for white supremacy. You’re a model minority until you’re not. Then you become an example. Your inaction has clear consequences — if Officer Tou Thao had intervened, perhaps George Floyd would be alive. He made his choice and he’s going to pay the price.DO THE RIGHT THING AND BE JUDGED FOR YOUR ACTIONS.

- Hmong Brothers, We Are The Problem: Domestic Abuse in Hmong Society

When it comes to domestic abuse, we are the problem, but we can also be the solution if we’re willing to listen.Growing up a Hmong man, I never had to think about or consider many of the issues that my sisters and female cousins had to navigate every day of their lives. In the current atmosphere of rising Hmong feminism, it’s brought to light many topics of abuse and injustices that the women in my life have had to live with. For example, being a good nyab and adjusting to the scrutiny of living under your in-laws’ roof, being seen by our society as belonging to their husbands, and the amount of abuse that Hmong women are only now publicly talking about.I grew up with the set expectations that I should be a protector and provider for my family; however from my father’s time to mine, I feel that definition needs to evolve into something greater. In my father’s generation, gender roles were clearly defined. Men were hunter-gatherers, while women kept the home fire alive, prepared meals and cared for the children. Men made the critical decisions regarding the family unit and the clan as a whole, but now as genders are finding more equal footing outside of Hmong society, inside we struggle to balance these roles and the issues around them. Additionally, we find that what once happened behind closed doors can no longer stay hidden. Women’s voices and their struggles can not and should not be ignored by Hmong men.There is a lot of pride that Hmong men carry — and rightfully so — for the many things that we’ve accomplished. Hmong men were stealth fighters in the Secret War. Hmong men paved the way through jungles and across rivers. Hmong men held up Hmong society in the hills of Laos, within the refugee camps, and in the resettlement into American society. All these things we should be proud of, but we must also open ourselves to evolve with the times and to listen to our fellow tribeswomen.When women voice their issues such as domestic abuse, one of the common defenses of men is that “domestic violence is gender neutral...men can also be abused.” Simply saying that “men can also be abused” trivializes the issue. It’s the male-equivalent of “all lives matter.” Women aren’t saying that men don’t get abused, what they are saying is that women are getting abused at a disproportionately high rate. Full stop. This is not a fact that’s up for argument — women are literally being killed. We’re not trying to debate the numbers — we’re trying to put a face to the statistics. The truth is that when it comes to domestic abuse in the Hmong community, the majority of abusers are men and the majority of victims are women and children.If you add in all of the variables such as rape culture, toxic masculinity, patriarchal rule, and systemic misogyny, then the most visible victims are women. Don’t get me wrong — men are victims of this patriarchy as well, but we are in a privileged position and should not be stepping on the backs of abused women in order to bring light to an issue that affects just us, the privileged group.It’s important to listen to the other side. I agree that the final goal is to address domestic violence across the board. Women and men are victims of domestic violence, however let’s tackle the most immediate concern and push to save the lives of those who are the most oppressed: our fellow women. They’ve been subjugated to being second class people, and it is our duty as the warriors/protectors/leaders that we claim to be to hear them and protect them as well as to ensure that Hmong women’s voices have equal share at our tables.

Vlai Ly

Vlai Ly

Hmong American photographer and writer. Owner of Letters to the Mountain and editor-in-chief for maivmai. Tell your story.

- My Spirit Dances: Hmong Shamanism’s Enduring Power

My father reminds me to cut the pork into thin slices for the stir fry. As I cut, My cousin hands me another beer. We’ve been cutting meat all morning as my mother and aunts cook on the patio. It is almost lunch time and soon we will gather at the table to thank the shaman for helping our family. I can hear the shaman jumping and chanting on her shaman bench inside the house, the gong’s clashing and finger bells’ chimes bringing her deeper into a trance.These mornings have always been a part of my life: waking up at 6 AM to help pick up the pig from the farm. Unfolding the long white tables in the backyard to cut the meat. Refilling the propane tanks and grabbing a few cases of beer from the store.As a child, I still remember the initial shock of seeing my father and uncles kill a pig. I still remember observing my mother as she killed a chicken, draining its blood into a bowl as its body went limp. Whether I am with family on the east coast, west coast, midwest, or the south, preparing for the ua neeb or hu plig ceremony has remained a part of our livelihood.As a Hmong child growing up in the United States, these ceremonial experiences always seemed strange to me. At school we pledged allegiance to “one nation under God”. From the churches at every street corner to the holidays we celebrated, I understood that this country was a christian country. Shamanism was not something I could share beyond my immediate Hmong community or else I would feel even more alienated than I already did as a Hmong boy growing up in Massachusetts.As I grew older and learned more about my Hmong history and people, I began to understand shamanism better. There were two experiences that really defined this understanding. The first experience taught me to step away from the atheism that developed in my frustration against America’s perspective on shamanism.I was at a Hmong wedding for a couple who practiced christianity. Before we ate lunch, their father called everyone into the living room to pray.In the past, I closed my eyes but did not actually engage in the prayer. As everyone closed their eyes and lowered their heads, readying themselves for prayer, I became aware of the same old judgment and criticism that I placed on these moments.I questioned my behavior and decided let go of my judgement. I closed my eyes and allowed myself to feel their father’s words. I allowed myself to feel the love and energy of everyone in the room as we gathered for the couple.From that experience, I understood that spirituality was not a matter of whether the god we prayed to was the right god, but instead it was about the full giving and receiving of trust and love to those around me.In shamanism, it is not only humans and animals that have a spirit. From the trees to the rocks, to the materials of our modern world, to the universe around us, everything has spirit so everything is honored. The most honored are our ancestors, who are not part of the past, but rather exist beside us and guide us.It is this belief system that guided my parents and grandparents through the Vietnam War. As I learned more about their history, I gained a deeper understanding and appreciation for shamanism’s impact on their lives.Growing up in the United States, school taught me to emphasize rationality and logic as the basis for success in life. But for my parents, the death, bloodshed, and loss of home that they experienced during the Vietnam War was not an experience that was processed rationally or logically. It was a visceral and emotionally devastating trauma that stripped life of meaning and catapulted my family into chaos. The stability needed to nurture a healthy sense of normalcy was gone and was instead replaced by the singular goal of survival.During this time of survival, shamanism provided a sense of rootedness for my family to maintain a semblance of stability. Ancestral prayers would guide them through uncertainty and bring forth a sense of peace. Combined with the love and support of the family and relatives around them, they were able to journey towards an unknown future as they made their way to the refugee camps in Thailand.Shamanism, as with all spiritual practices, provides people with a story and mythology that guides us through difficult times in our lives. Without an overarching story and mythology, we can become lost in the inherent chaos of life.I am thankful that my family still practices shamanism. I am thankful for the relatives who gather to help the ua neeb and hu plig ceremonies. Beyond the spiritual ceremony itself, the community is central to the healing process. According to the journal Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, the relationships we retain and nurture allow us to live longer and healthier lives. This is something I notice within my own life, how my ongoing relationships from childhood has given me meaning and purpose to each day.Shamanism, combined with the support of the community, is what carried our parents and grandparents through the Vietnam War. It provided a sense of hope, meaning, and purpose as they took care of one another. It continues this provision within our present lives here in the United States. Whether I am cutting meat all morning or simply there to support my relatives, I am reminded of the importance in humility and service to others.As I navigate adulthood in America, it is easy for me to find myself in a constant state of busy work. On one hand, this country demands that drive and individuality to succeed, but this leads to isolation and a suburbanization of the self as we move further and further away from one another — physically, emotionally, and spiritually.Hu plig and ua neeb ceremonies offer us a space to reconnect. Once the shaman has completed her rituals, we gather at the lunch table and bow down to thank the shaman for her help. The process of lowering ourselves to the floor communicates our humility and respect, and it is when we lower ourselves in service to others that we are most rooted.The shaman serves us and we serve her in return. The community serves us and we serve the community in return. It is this exchange that unites the community and provides us with healing and blessings. Shamanism allows us to pause from our busy lives, reconnecting with our Hmong traditions, and honor a history and culture passed down for thousands of years.

- Discovering What it Means to be Hmong American

In honor and dedication to my Grandmother, See Vang, (May 2nd, 1921 — July 13th 2021)This is an excerpt from an article originally published in Txhawb MagazineMy grandmother never talked about herself when I ask about her life back in Laos. Instead, her stories always revolved around the people she loved. Sitting alongside her in my uncle’s house in Fresno, she tells me of the time my father was almost left behind in Laos during the evacuation.“We all got in the car but there wasn’t any room for your dad. He was just a little younger than you, just standing up there on the road while we were all about to leave. Your grandfather called his name one time, called two times, but he didn’t hear. He called a third time, then finally your father came down very quickly right when a soldier’s truck came. He was able to get in that truck with them. That’s how he got to come. If that wasn’t the case, your father would’ve been left behind.”My grandmother amounted it to luck, and as I sit here writing this, I have to consider that maybe she was right. There were so many loved ones who didn’t make it out Laos, like the parents whose children my grandmother took in while going to Thailand.“Wherever the kids go, I go also. We came this far, why would we let children go become orphans? I won’t let.” My grandmother recollected.No one gets left behind — these were her sentiments towards everyone around her as a war waged on. Her struggle was their struggle. Her triumph was their triumph. Her life was their life.Photo taken by Henry VangIn listening to her stories, I came to understand the seed that existed inside our hearts, a seed that I have inherited within this new generation as a Hmong American. This seed is the idea that our lives are not our own — that we create community and community creates us.As gunfire exploded around them and airplanes ripped through the sky, Hmong people drew their strength from that sense of community. When they had to flee from their villages, it was other Hmong people that provided them a new home to travel with.You can see this within the United States today. From California to Massachusetts, we congregated together because Hmong people provided that familiarity and comfort as we started to build a new life in a new land. Home is often thought of as a place or a location, but to Hmong people, home is the people themselves.Photo taken by Henry VangMy life is a continuation of my grandmother’s story— of the Hmong story. To know her story is to know of the seed of community that exists inside me. Regardless of whether they are family or strangers, I remind myself to be there for everyone, to struggle and succeed together like my grandmother did with those around her when they came to this country. For me, to be Hmong American means to uplift the people around me so we can see the value in our story, as individuals and as a community.Photo taken by Henry Vang

- Khi Tes: The Strings That Bind Us All Together

There is an idea that there is no real concept of “self” within the Hmong culture — that we live our lives as a collective whole. And when I stand in a room with my wrists raised for all my relatives to tie a string to, I feel that collective nature at its strongest.Strings were tied around my wrist when I was born. It was part of the hu plig ceremony to welcome me into life, where a shaman stood at my doorway and recited a chant to call forth my soul into my body.The smell of incense filled our duplex, its trail of smoke rising from a bowl of uncooked rice that held the sticks in place. Next to the door was a chicken that was bound by its feet, its life soon to be sacrificed in exchange for the safe arrival of my soul.When the shaman finished, my parents carried me to a table where all of my relatives then crowded around us, tying a string around my wrist as they recited a blessing.My whole life has been a process of holding up my wrists to have these strings tied around them. Sometimes they were decorative — thin red, black, and white strings twisted together to become one, and it would just be that single string upon my wrist. Sometimes they were just a plain white cotton yarn but with dozens running up each wrist, like the strings I received as a newborn.The strings are meant to bless me and to place good fortune upon my life, but as I’ve gotten older—and when I really pay attention to what’s happening in that room—I begin to see the real meaning in the beauty of the strings.The meaning stands in juxtaposition to who I am as an individual. I grew up always searching for this need to be free, and this freedom came through a process of self-discovery. But the irony of my self-discovery was that—it was not a matter of selfhood—but instead a matter of realizing just how many things outside of myself I was truly rooted into.The strings have come to represent that sense of rootedness. A rootedness to things beyond myself, things bigger than myself—more important than myself: My family, my friends, my community, my culture, my people. Our history, our heritage, our beliefs, our story.And when my inner nature makes me feel alone within my journey, the strings remind me of all the things that I am rooted into. The strings are more than my relative’s blessings over my life. They are my relatives themselves. They are my family, my community, my culture, and they remind me that I am part of a story that is so much bigger than myself.There is an idea that there is no real concept of “self” within the Hmong culture — that we live our lives as a collective whole. And when I stand in a room with my wrists raised for all my relatives to tie a string to, I feel that collective nature at its strongest.It is a powerful feeling to know so intimately the collective story of everyone in that room, of how not even 50 years ago we had lost our homes to war, but somehow came together and found a sense of home amongst each other.It is a home that cannot be revoked, a home that we cannot be exiled from, a home where there is no displacement because it exists everywhere. This home is our collective story, where my story is a continuation of my parent’s story, and their story is a continuation of their parent’s story. And a beautiful web develops within the community because we understand one another’s story without ever needing to state it.The strings around my wrist are tied into an infinite loop. They are a never-ending reminder that my story is not my own, but instead one that is shared between all the people inside of that room. The strings I receive possess the same meaning and blessing found within my relative’s own strings—the same meaning and blessing found within your’s, the very string tied around your own wrist that binds you and me together.Khi Tes: The Strings That Bind Us All Together was originally published in maivmai on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

- Xijiang Woman Cleaning the Village

We have to figure out what kind of stories we want to tell, and whose stories we want to tell. I often draw parallels between my trip to China and Laos with Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist. In The Alchemist, the main character — a shepherd boy — embarks on a journey far away from home in search of a treasure that appears within his dreams. However, when he reaches the supposed spot of the treasure, he learns that the treasure was buried in a church in his village all along.It took me a trip across the world to realize that my artistic muse within photography and writing are the people back at home. But not only those close to me, but everyone who I cross paths with; everyone who I’ve had the pleasure of observing in their daily lives. This epiphany came to me when my presumption of being connected to these almost-mythical lands was debunked. I thought I would find a home in China and in Laos through a spiritual connection from my Hmong heritage, but what I found instead was a home in people’s untold stories that they lived out right in front of me.I saw this Xijiang resident on my way to get breakfast and I took a photo as she was picking up trash from the sidewalk. All throughout the village are these ladies wearing these blue raincoats who are picking up trash that the countless tourists drop as they explore the village. While their language almost sounds so similar to the Hmong language, there was no way to actually communicate with her. But I wanted to know her story. I wanted to know what her life was like here. I wanted to know her struggles and what she loved most in life.But the tragedy is that, for her and for a lot of people I know, including myself, we think of our story as insignificant. We think of our story as something not worth telling or speaking about. I struggled with this for my whole life as I compared myself to the glamours of our celebrity culture, not realizing the beautiful poetry of our everyday lives.While I am slowly crawling out of this psychological deficit that I’ve placed over my life, I still have to remind myself that I do have a story worth telling and so does everyone else around me.

- Anathemas, Atrocities

- January Prompt: Resolutions, Metamorphosis

Photo by José Ignacio García Zajaczkowski on Unsplash“Near the end of its growth cycle, the caterpillar consumes many times its own weight in a single day. Then, the caterpillar finds a branch from which to hang, and its skin molts off, leaving a glistening chrysalis. Inside this hard-shelled pupa, the old caterpillar identity starts breaking down. ‘Imaginal-cells’ of the ‘butterfly-to-be’ emerges and struggles with the caterpillar’s immune system. By clustering together, the imaginal cells overwhelm the collapsing caterpillar and feed on its remains as nutrition.An original creation forms from inside the chrysalis with an entirely new nervous system, digestive system, heart, legs, and wings. The butterfly must squeeze out from its protective shell in order to force fluids from its thorax into its wings. Without this final struggle the butterfly cannot survive. The butterfly’s miraculous metamorphosis and powerful will to emerge into the light has come to symbolize the journey of the soul.”- Alex Grey, Net of BeingThe start of a new year presents us with an opportunity to become better than we were last year. This evolutionary process from our old self to a new self is symbolized through the caterpillar’s metamorphosis into a butterfly.For this month’s prompt, tell us of a metamorphosis that you or someone has taken that changed them for the better. This can be a resolution that you’ve committed yourself to for 2019, a metamorphosis you’ve tackled in the past, or the story of a journey filled with struggle, triumph, or tragedy that befalls a character.All submissions should be in before January 25th. Your stories will be shared on the publication and Facebook page shortly after the editors have reviewed and published your story.January Prompt: Resolutions, Metamorphosis was originally published in maivmai on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

- A Mother’s Work: My Mother’s Life at 50

Our first home was a tiny duplex right on the outskirts of Six Corners, one of the most impoverished neighborhoods in Springfield, Massachusetts. Squeezed into the tiny apartment was me, my four older sisters, and my parents who were still very young — if not in age then in knowing how to navigate a then-unfamiliar country that they called America.My mother married my father at a young age and then had my siblings and I shortly thereafter. Her life as young refugee mother was difficult in a low-income community with limited opportunities. She wasn’t able to finish high school and faced an English language barrier as a Hmong refugee.Her best option early in our lives was to work a rotating schedule with my father so she could both make money and take care of us at home. As my siblings and I grew older, the duplex grew too small to hold a family of seven and my parents knew that it was time to find a larger place to live in. After their tireless effort of working a job and taking care of us, we eventually moved into our current home located in a safer part of Springfield.Over the years, the duplex was eventually demolished and replaced by a community center, but to this day it still serves as a reminder of my mother’s tireless work that she put into forging a better life for us.Despite her struggle with the English language and the never-ending work of being a young mother of five, she eventually attained her associates degree and began working as a Nurse’s Assistant. However, her income combined with my father’s income was still a struggle for the family in our early years.So, my mother, on top of raising five children and being a Nurse’s Assistant, began working from home as a textile worker late into the night until it was time for her to sleep for work the next day.Every night I would watch my mother pull at the long pieces of fabric yard by yard, meticulously scanning the surface for tiny knots to be pulled out with a needle in hand. After she reached the end of a load, I would help her fold the fabric for what seemed like a hundred folds and then help her carry it onto the carts in the garage. We would then carry in a new load for her to restart the whole process for the rest of the night.On the weekends, an 18-wheeler would squeeze its way through the neighborhood and pick up the carts of fabric, leaving her with a whole new batch of fabric to go through for the following week.During the school week, my mother would wake up me and my sisters as we dragged our feet out of bed to get ready for school. She constantly rushed us along so we wouldn’t miss the bus, all the while getting ready for work herself and making sure that we had something to eat before stepping out of the door.After she was done with work, she would then rush across the city to pick us up from sports practice or our after-school activity. Sometimes we got frustrated whenever she was late, not realizing just how much of an effort it was to pick us up right after a long day of work.And then when we got home from school, my mother would always make dinner for us to eat, afterwards trying her best to help us with our homework all while juggling her textile work.This was my mother’s life.Through all of this backbreaking work from daytime until night time, the one thing that continued to radiate from her was an immense sense of love for my siblings and everyone around her.There was never a moment where she wanted to call it quits. There was never a moment where anything was just too difficult for her to handle. She didn’t blame other people when things went wrong. She took full responsibility for the new sets of struggles that kept coming and found a way through.It is this sense of love, patience, and kindness that guides my mother’s life. She accepted every moment, struggle, and person as they are. I knew that her life was a constant struggle filled with work and stress, but I never saw it on her because she handled everything so effortlessly.I remember coming home from middle school one day when my mother asked me and my siblings to go downstairs for a little while. Confused at the random request, we obliged and waited in the room where my mother did her textile work. After a little while, my mother opened the basement door and told us that we could come upstairs now.My sisters and I made our way upstairs and into the kitchen area. Once we were all upstairs, we saw that the kitchen table was decorated with candles, cookies, and food for us to eat as a Valentines surprise that my mother threw for us.That immense sense of love that my mother showed to us that night only continues to grow for her family and the communities around her. Every weekend she is out with my father at community events, driving hours away to support the Hmong organizations across Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. The smile and joy that she possesses on her face at these gatherings is genuine. It is a smile that I see at community celebrations and also a smile that I see at home when she is just with the family.I still have so much to learn and cultivate from my mother’s life. From her resilience as a young refugee mother of five living in a tiny duplex, to the compassion that she gives to the larger community around her.My mother is a shining example of living a life beyond herself and one that is led by her heart.She is all at once a lover and a fighter, qualities that my siblings and I have inherited in our own journeys through life. Beyond any of our accolades or accomplishments, the biggest gift that my mother has provided for my siblings and I is the inheritance of her spirit and heart. She has taught us that the biggest priority in life is to become a good person first, and then any external pursuit of greatness can follow thereafter.Yesterday, my mother turned 50 years old and we filled up an entire room at a restaurant to repay her for all the love she’s given us over her lifetime. During her thank-you speech to everyone, she mentioned the importance of cultivating an unconditional love towards the world. To simply speak about the idea of unconditional love is easy to do, but to actually accomplish it through the way you live your life is extremely difficult. But for my mother, who has forged a beautiful life from our days at the duplex to each new morning that arrives, she accomplishes this virtue so effortlessly.These words will always fail to capture the immensity of the person that you are, but you have always been a beacon of unconditional love to everyone around you. Thank you for all the work you’ve put into providing this beautiful life for us, happy birthday mom!A Mother’s Work: My Mother’s Life at 50 was originally published in maivmai on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

- The Possibilities of Who We Will Become

The Possibilities of Who We Can BecomeBut here I was, holding a beautiful anthology of work written by my own people whose words revealed to me the possibilities of who I can become, beyond all of the limitations and fears that were placed on me growing up.I remember walking through the cluttered roads of the Fresno New Years when a wall of books stopped me in my tracks. Intrigued, I started thumbing through the various books, both written by and about Hmong people.Some books confounded me with their endless paragraphs of Hmong sentences touching upon various cultural subjects. Other books I knew about, such as The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, which had become the cornerstone of America’s understanding of the Hmong people.I continued up and down the row of books, skimming quickly through them, until I landed upon a book that posed a question on it’s cover:How Do I Begin?It was 2014 and I was 4 months away from graduating from college with an English degree. I was in the tail end of finally healing from a terrible break up, and I was ready to move towards all of the new beginnings that presented themselves to me.How Do I Begin? A Hmong American Literary AnthologyI held the book in my hand and began reading through the poetry and prose that filled all of its pages.“Once, American poets were bornin the factories of Detroit,” began Soul Vang’s poem Here I am.I continued reading further into the anthology, slowly becoming engulfed in the stories that unraveled themselves before me.“Tomorrow, I will smear blueacross the skies from mountain to mountainand scrape the rivers from their bellies,cup my hands to your mouth,so you can drink the love I beg.” ends another poem, Dear Father, written by Khaty Xiong.In all of the stories and poems that I read, I saw a sliver of myself in a way that I never had before in my English literature courses.I never knew the possibility of becoming a Hmong American writer until that fateful day. But here I was, holding a beautiful anthology of work written by my own people whose words revealed to me the possibilities of who I can become, beyond all of the limitations and fears that were placed on me growing up.I pulled out a twenty dollar bill and handed it over to the vendor and brought the book home, keeping it close to me ever since, reading it whenever I needed ground myself amongst the chaos of this American life.In starting maivmai alongside Chelsey See Xiong and Lilian Thaoxaochay, I wanted to continue the impact that the Hmong American Writers Circle has had on my own life. Growing up, I never knew that I had a story to tell. I always believed that my life was unimportant But the Hmong American Writers Circle paved a path for me to discover the importance of my own story. maivmai wants you, all the readers and writers, to honor your story as well by writing it into existence—so how will you begin?The Possibilities of Who We Will Become was originally published in maivmai on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

- A Seat at the Long Table

I remember crying the first time I drank beer. I was maybe 12 or 13 years old and I was at my uncles house for a hu plig ceremony. I was standing next to my father and we were in the dining room alongside all of my uncles, the two of us nudged into the middle of this group. All of us were thanking the grandmother who performed the ceremony when an uncle pulled out a beer can and a small glass cup.I didn’t think anything of it because I’ve seen this so many times, but when it got to my father and he finished drinking it, he poured a small amount into the glass and stretched it out to me.I looked at the glass and then up at him, who then signaled to me softly and welcomingly with a smile to take a drink from the glass.“Haus me me xwb.” (“You only have to drink a little bit.”) He said.With all of my uncles now watching me, I subtly shook my head back at my father to signal to him “No thank you” in an attempt to hide my rejection of the drink away from my uncles.But my father’s hands didn’t lower. The tiny glass of beer didn’t magically move away from me. My father didn’t concede to my rejection of the drink and his hands didn’t budge like I wished it would.Instead, we stood there in silence as all the uncles watched us. The glass cup stood eye level to me as though it was looking into my soul, my frustrated and anxious soul as I realized that there was no rejecting this small sip of beer. I looked at him one last time and then back at the cup as tears started streaming down my face.I took the glass from my father’s hands, my own hands shaking as I now took full possession of this drink. It was mine now. There was no returning it to my father and there was no handing it off to the next person. The only way to get rid of the cup was to now drink it.I held it in my hand for a while, thinking about all the horrible tastes I would have to force upon myself.Will I spit it back out onto this floor? Will I throw up? What will it taste like? Fish Sauce? Stale cardboard? Other people’s spit? All these ideas running through my head as all these eyes watched me cry.But the anxiety inside of me gave way to the anxiety of stalling for so long as my uncles and father watched me.I lifted the glass towards my mouth with my eyes clenched shut and I swallowed the drink as best as I could without having to taste it. When I opened my eyes and came back to reality, all of my uncles and my father started to snicker at me as I realized how much I overthought the whole thing.I wasn’t drinking snake poison. It didn’t taste disgusting and there wasn’t this need to throw up.My father rubbed his hands against my back to let me know that I was okay. He reached his hand out for the glass and I handed it back to him. He refilled the it for the next uncle in line and I watched the beer spill over the side of the glass and onto the floor.The beer always seems to spill. It always seems to spill all over the sides, sloppy and unsteadily into the cup as one person pours it to the next person.“Hliv kom zoo nkauj.” (“Pour so it looks beautiful”). They would always say that to us at the table whenever a glass of beer was being passed around.Pour so it’s beautiful.I love this phrase because to pour beautifully doesn’t mean to pour so it doesn’t spill all over the place. It doesn’t mean to be steady and tidy as you pour. It means to make sure that it DOES actually spill if it has to. To make sure that it spills onto the plate and onto the floor and all over the cup and all over your hands. It means to make sure that the cup is full, brimming to the top so the person you pass it to can be as full as the cup.And at 26 I realize that to be as full as that cup is to be full of the love of the people that surrounds you, and to return that love to them.My father told me that the most important thing about being Hmong is loving the Hmong people. Beyond our immediate circle of friends and family, this idea about “loving Hmong people” isn’t an easy task that comes naturally to us.It’s not natural to love people just because their the same ethnicity as you. because a lot of these people are different and they think differently from you. They live lives that you may not want to associate yourself with. They do things that you may not enjoy doing. In the scope of all of these considerations, criticism seems to be fair and natural to us, but I know of the love that my father speaks about when hesays that to me.My parents have always presented their love towards me and my siblings as a submission of power. To lose power and to give up their control over our lives and accept the individual paths that we decide for ourselves. They choose to love us regardless of what decisions we make and regardless of the mistakes that we will continue to make it in life.This love that my parents presented to us is the love I actively try to show to Hmong people around me, because regardless of whether I know you or not, I consider you family.Regardless of the tension between us or the differences we may possess, I know exactly how you got here today because it’s the same way that I got here today. Our history and our struggle is the same and our grandparents and parents came to this country linked arm to arm. And faced with seemingly insurmountable odds, they were able to overcome it with the knowledge that they were surrounded with a community bearing that same struggle alongside them.All I’ve ever known is that I am just a continuation of the people that have came before me. My ancestors, my grandparents, my parents, my siblings. And all I want to be is a precursor to those who will come after me. My little brother, the Hmong youth, those who will be due in a few weeks or months and the kin that will come in the next few years, decades, or centuries.To live in this manner, to accept everyone around you regardless of their ideas and lifestyles is a challenging and never-ending. To work past our pretenses and notions and ideas and learn to love those around us who are different from us.As we live in America, we become so engulfed in status, and career, and finances, and all these external things to us that it’s so easy to lose sight of what really fulfills us on the most essential level. And maybe this idea of “fulfillment” is different from person to person, but I always like to imagine what I would cherish the most at the end of life and ground myself into those values.My family, my community, my identity. The people close to me and those who are far. The people I teach myself to love despite the differences between us. All of the answers always revolve so closely around people.I never want to belong to a circle of like-minded people or a group that I feel is just like me that I vibe with completely. I want to be a part of everyone, to be a part of everything because I see so much of myself in the people around me and I see so much of them in me regardless of how similar or different we are.Their accomplishments. Their failures. Their happiness. Their struggles.All of that is so familiar to me because I possess all those things. And sometimes when I drink with my brothers and sisters, my aunts and my uncles, my mother and father and everyone around me, this mixture of feelings comes knocking on my door and I am obliged to open and welcome it in and embrace it all the same.The accomplishments are the same as my failures. My happiness is the same as my sadness. The easy days are the same as my hardest days and I want it all because there is no true separation between them. They are just different degrees of the same thing across one spectrum and the untidiness of it all fills my cup to the brim.A Seat at the Long Table was originally published in maivmai on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

- Let Me Linger in This Lilac Field Forever

I thought he loved me, but he killed me

Today is October 13, 2019. Light, white, glistening snow has started to drop. It is cold and gloomy in the twin cities Minnesota. I am bless to have another day with my three kids and family. I am filled with gratitude. However, across the bridge, 15 miles from here, the sorrow and discontent of a family is felt. It rings throughout their homes and into my heart. Instead of having lunch with her, they instead is mourning her. This family has lost a daughter, a sister, a niece, a friend, and a mother to …. not an illness or an accident…..but to a heartless, senseless, selfish, vicious crime…DOMESTIC VIOLENCE. DOMESTIC VIOLENCE at the hands of her one and only husband. Her once, her one true love. Her once, her protection. Her once, her future.

This is an all familiar story in all of our community. The rising question is always and usually , “What happened?” “Who did what?” “WHY?” I believe these are the wrong questions. The 3 “W’s” does not work here. The 3 “W’s” does not find solutions …it instead only creates curiosity without solutions.

IS there a solution? Perhaps…that is the most compelling question. Is there? I, we, they, will never know for sure. However, we have to start coming to the table and brainstorm ideas on how we can help. This table that is yearning for ideas, solutions, change, has room for EVERYONE. Not just women or men. It is a table yearning for all walks of life: men, women, children, elders, LGBTQ, all status, EVERYONE. Often times….these tables would go unnoticeable…empty seats…no body wants to fill them. But when an incident happens, all questions arise. If the table is too big … how about we start here.

Start conversations with your family, your children, educate them about domestic violence. What is domestic violence? How to recognize abuse? What to do? What does LOVE truly look like? If you’re experiencing rage, what to do? We all have a responsibility to partake in these conversations.

If you are on the fence about this….ask yourself…..if that was my sister, my mother, my friend in that coffin today…..how would I feel?

-Mai : a concerned mother, daughter, sister, friend , auntie

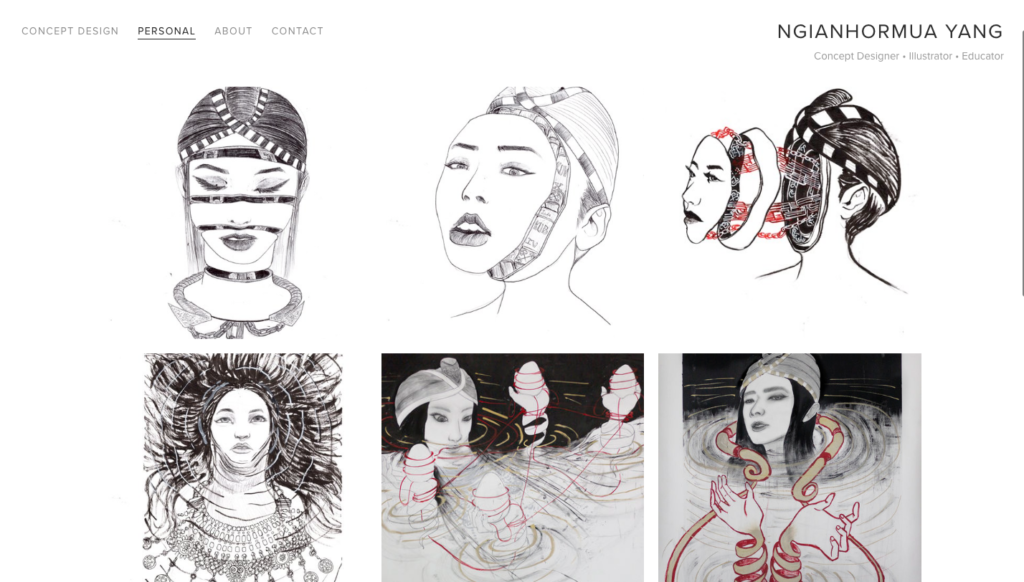

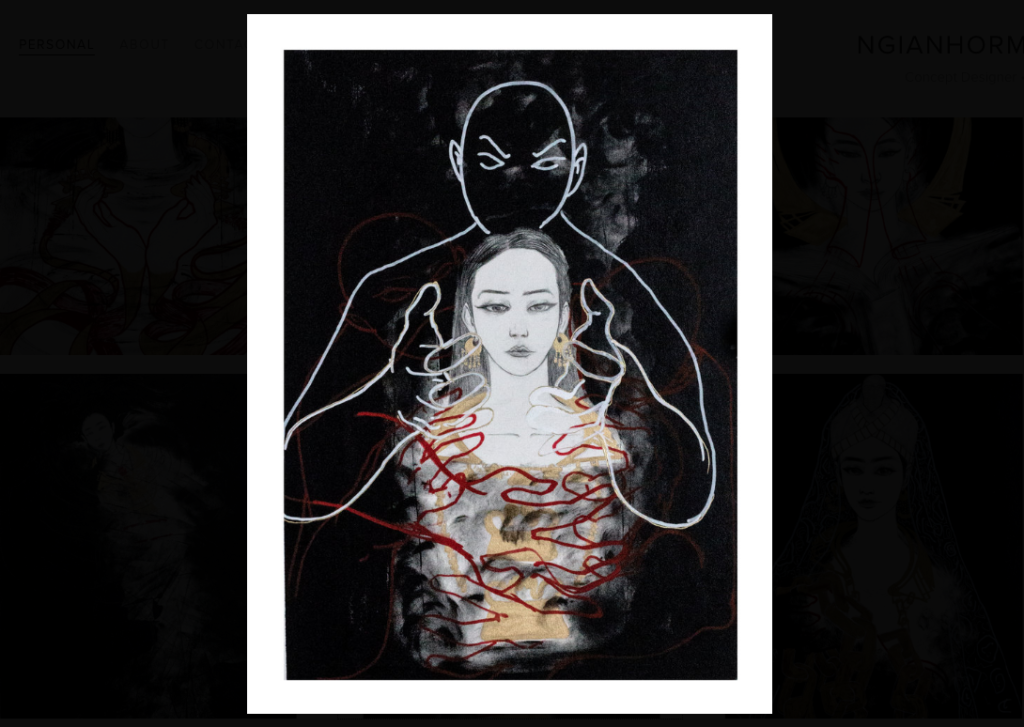

PHOTO CREDIT: WWW.NSYART.COM